Unity serialization part 2: Defining a Serializable type

This post is part of a series about Unity serialization. Click here for part 1: how it works and examples.

On the last article, we discussed about serialization concepts and how Unity implements it, learning which types can be serialized and which cannot. But what if we want to define our own type? How can I make it serializable so I can keep its data stored?

Understanding the problem

Let’s choose a (slight biased) model to implement as our example: a script to keep all the data to an investigation game which contains numerous cities, each one containing several places. Sounds pretty easy and straightforward, so let’s do it naively by creating MonoBehaviours: one for the database, one for the cities and one for the places. That should work:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public class MyDatabase : MonoBehaviour

{

public List<City> cities;

}

public class City : MonoBehaviour

{

public string name;

public List<Place> places;

}

public class Place : MonoBehaviour

{

public string name;

}

There, done! But wait a second, something’s wrong: I can’t just create an instance of a MonoBehaviour, it should be attached to a GameObject and I don’t want to create a one to each instance of a city or place. Something is wrong conceptually. It happens that we can’t think of that data as behaviors, because they are not. They are simply objects, just like good old object-oriented programming. So let’s go ahead and take the MonoBehaviour inheritance from the City and Place classes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public class City

{

public string name;

public List<Place> places;

}

public class Place

{

public string name;

}

Now let’s add the MyDatabase script to an object in the scene. Something is wrong again: I can’t see the list of cities in the inspector even though the field is public and should be serialized (therefore shown in the inspector).

Defining a Serializable Type

That happens because we didn’t define our type as serializable, so Unity won’t serialize it. We never faced that problem before because we usually deal with classes that inherit from Unity.Object (Collider, RigidBody, Animation, MonoBehaviour…), which is a serializable type. There is an easy way to do it: add the System.Serializable modifier to the class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

[System.Serializable]

public class City

{

public string name;

public List<Place> places;

}

[System.Serializable]

public class Place

{

public string name;

}

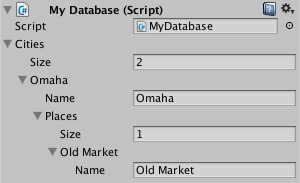

That gives us the expected result:

By simply adding that modifier, we mark our class as serializable and solve our problem. The same process is also required when dealing with structs (serializable since Unity 4.5). In addition, Unity also serializes lists and arrays of serializable types by default.

Problems with that approach

Although this looks like a great solution, there are a few problems with it. The first (but not biggest) is that even though MyDatabase only stores data, it still is a MonoBehaviour and needs a GameObject to exist. Ideally, it should be an asset that only holds data, but we can’t simply take the MonoBehaviour inheritance off the class, otherwise we wouldn’t have a way to serialize it. What if there was a serializable type just like MonoBehaviour that doesn’t need a GameObject to live on? Keep that in mind. The other problems doesn’t involve data-storing objects only like the first one, but are also valid.

The second problem involves polymorphism and happens when a class inherits from a user-defined serialized class. Even though it’s intuitive that fields from both classes should be serialized regardless, that doesn’t happen. Let’s use the same example as Unity blog does: animals.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

[System.Serializable]

public class Animal

{

public string name;

}

[System.Serializable]

public class Dog : Animal

{

public string breed;

}

public class PolymorphismExample : MonoBehaviour

{

public Animal[] animals;

}

Even though both Animal and Dog classes are serializable and Dog inherits from Animal, if we add a dog to our list of animals in PolymorphismExample, they will be serialized as instances of Animal, losing the Dog type and consequently its fields. What if user-defined classes supported polymorphism? Again, keep that in mind.

The third problem is related to decoupled references, which is a fancy name to something really simple. Imagine you have the same Animal example as the problem above and you add 3 animals to your array, but all of them point to the same object. Due to how Unity’s serialization works, these references are decoupled and they are serialized as three different objects, hence changes made to any of those three objects won’t affect the other two. Unity simply forgets that those objects point to the same reference, which can be devastating to systems that keep complex relation between objects of that class.

The decoupling problem happens because these fields (primitives and user-defined) are serialized “in line” since they are actually part of the MonoBehaviour’s serialization data and not a data object itself. With objects that derive from Unity.Object though, the fields are serialized as actual references to the object, and not “in line” like custom classes. What if we could use a class that derives from Unity.Object, serializes the objects as references and maintains complex relations between our objects?

The last problem is related to recursive declarations, which can generate cycles. Consider this example:

1

2

3

4

5

[Serializable]

public class DepthClass

{

public List<DepthClass> depthObjects;

}

And a MonoBehaviour that holds a reference to an instance of it:

1

2

3

4

public class DepthTest : MonoBehaviour

{

public DepthClass test;

}

How many allocations will be done to serialize an uninitialized DepthTest script? The intuitive answer would be 1 – a null reference – but it happens that the Unity serializer doesn’t support null references of custom classes so it creates an empty object and serializes it instead (this is transparent to the user). And since this object is created and it has a reference to a list of objects of its own type, it creates a cycle in the serialization process that should go on forever. To prevent this cycle (for real, it’s not a joke) the Unity guys picked the – magical – limit of 7 depth levels and after reaching that level, the serializer will assume that a cycle was defined and will stop serializing fields of custom classes. What if we could use a type that supports null in the serialization pipeline?

Each problem described above has a potential solution and It turns out that all four can be fixed with the same resource: ScriptableObject. It’s not an extremely elegant or ideal solution, but it’s the closest we get from one. Since it’s a fairly long subject, Scriptable Objects are described in depth on my next article. For now, let’s just acknowledge that those problems have a common way out and if you believe you may face one of those, take a look into it.

Modifiers and Serialization

Finally, let’s summarize the modifiers involved in serialization.

- Use

[System.Serializable]on a class or struct definition if you want it to be serialized. - Publics fields are serialized by default, but only if its type is serializable (constants, static and readonly fields are not serialized).

- Use

[SerializeField]if you wish to serialize a private field. - Use

[NonSerialized]if you want to avoid serialization on a public field. - Use

[HideInInspector]if you want to serialize but not expose the field in the inspector.

Conclusion

In this blog post we learnt how to define our own serializable types and acknowledged some problems that can emerge by doing it. On the next article, we will dive deep into a resource that can work out those problems: ScriptableObjects.

Comments

Great blog! Thanks! Its [SerializeField] not [SerializeObject] typo mistake 😉

Thank you, I just fixed it!