Unity serialization part 1: How it works and examples

This post is part of a series about Unity serialization. On this series of articles we will discuss a topic that is extremely important to Unity development: serialization. This subject may be a bit cloudy for beginners, but understanding it not only helps to figure out how the Unity engine works, but it can also become really handy during a game development process and assist you to build better solutions. We will concentrate our study on the following subjects:

- What is it? (part 1)

- How Unity does (part 1)

- Examples (part 1)

- Defining a Serializable Type (part 2)

- Problems with Serialization (part 2)

- Scriptable Objects (part 3)

Fell free to navigate through the sections if you are comfortable with the previous concepts.

What is it?

Among other definitions, serialization is the process of converting the state an object to a set of bytes in order to store (or transmit) the object into memory, a database or a file. In another words: it’s how you can save an object to restore its state for later use.

Let’s say you have a Vector3 and you need to store it for future use. Which fields would you save into a file to restore its state? x, y and z, that’s easy! Apply this rule for any object and if you serialize all the (important) data, you can reload the object exactly how it was before. We name the process of storing the state of the object as “serialization” and the reverse process of building an object out of a file “deserialization”.

As we already read, this process is really useful to store and transmit data, so think about this: you have an online store deployed on your server, probably running a database manager application aside. Eventually, we need to store the data from memory into the disk (primary storage is volatile) and we do it by serializing our objects into database tables (which basically are files). The same process happens with every application that needs to store data into a disk, and computer games (and engines) are not an exception.

How Unity does

Unity, as a Game Engine, needs to load a lot of stuff (scripts, prefabs, scenes) from the disk into the memory within application data. Maybe more important than that, Unity needs to move data between the native C++ side of the engine and the managed C# side. Even though we may think this task is strict to loading and storing assets processes, the serialization is used in many more situations than we think (like inspector window, reloading of editor code and instantiation among other scenarios). You can learn a bit more about Unity Serialization on their own blog. I’d risk to say it’s a mandatory read for developers.

The UnityEngine.Object class (which is serializable) provides us with the serialization resource in Unity: any other class than inherits from it – that includes MonoBehaviour, ScriptableObject (more on this later on the series), Shader, Sprite and basically everything in Unity – can also be serialized. Most of its uses are invisible and don’t matter when developing a game, except for a major use: scripting. When you create scripts, you need to keep on mind which fields you want to serialize, and, to do so, your field must:

- Be public, or have

SerializeFieldattribute. - Not be

static. - Not be

const. - Not be

readonly. - The field type needs to be of a type that we can serialize.

Which field types can we serialize? According to Unity’s documentation:

- Custom non abstract classes with

Serializableattribute. - Custom structs with [Serializable] attribute (new in Unity 4.5).

- References to objects that derive from

UntiyEngine.Object. - Primitive data types (

int,float,double,bool,string, etc). - Array of a field type we can serialize.

- List of a field type we can serialize.

A really common data structure isn’t serializable: dictionaries, even if you declare them as public, and SerializeField atribute. So keep that in mind when developing a game.

Ok, this is a lot of information, so let’s break it to a straightforward code example:

Examples

Let’s take the following code (MyBehaviour.cs) as an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public class MyBehaviour : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private int x = 3;

[SerializeField] private float y = 5.6f;

public float pi = 3.1415f;

private int mySecret = 42;

public static int myStatic = 10;

public const int myConst = 22;

public readonly int myReadOnly = 99;

public int MyProperty { get { return 100; } }

}

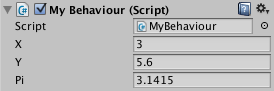

The only fields that are serialized are x, y and pi because they are not static, const, readonly, a property or private field with no SerializeField attribute. One way to show this is by taking a look at the script’s inspector, which only shows us serialized fields (that can come handy):

But there is a better way to show that the other fields were not serialized: by cloning the object. Remember I told you that the Instantiate method uses the Unity serialization process? So let’s test it by adding the following method to our script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

private void Start()

{

Debug.Log("Pi:" + pi + ". MySecret:" + mySecret + ". MyStatic:" + myStatic);

}

private void Update()

{

if (Input.GetMouseButtonDown(0))

{

pi = -4;

mySecret = -11;

myStatic = 13;

GameObject.Instantiate(gameObject);

}

}

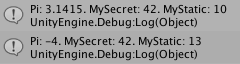

This method should modify the current object and create another object in the scene when the mouse’s left button is pressed. A naive thought would be that since the second object is a clone of the first one, it should have the same value for pi, mySecret and any other field as the first object, right? Well, it does for pi, because it’s a public field (hence it’s serialized), but it doesn’t for mySecret: its value remains unchanged when the second Debug.Log is executed:

The field mySecret can’t be serialized because it’s a private field with no SerializeField attribute (which is the only circumstance a private fields will be serialized*).

*: Private fields are serialized in some circumstances in the Unity Editor and that can lead us to some problems we will discuss later on the next article on the “Problems” session. (source)

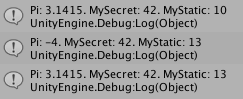

Curiously, the value of myStatic changes in both objects, but does that mean static fields are serializable? The answer is no. Even though its behavior leads us to conclude that, remember that static fields belong to the class, and not to an instance of it. That said, if we, per example, create a new object and add a MyBehaviour script to it in play mode (Using GameObject > Create Empty in the menu), myStatic will have the same value as the other objects, although it isn’t a copy of any other object. However, note that the pi field has its original value.

This proves what the Unity documentation tells us about how can we make a field of a serializable type be serialized. This works with most Unity objects, including MonoBehaviour, but what if I don’t want to define a MonoBehaviour and I still want to create a Serializable type? In other words, how can I define a Serializable type?

On the next article we will find out how to declare our own serializable types and how to treat problems that can come along with it. Fell free to write me any suggestions, errors, complements or just to say hi on the comments section. 🙂

Sources

- Serialization in Unity by Lucas Meijer (mandatory read)

- Unity Serialization Best Practices by Tim Cooper

- ScriptableObject (Unity)

- Serialization (C# and Visual Basic)

Comments

Thanks!

You arguing that “mySecret” doesn’t change, might be misleading, since you are logging ‘x’.

That’s a typo, I meant “mySecret”. I’ll fix it. Thanks!

I just fixed the code and the screenshots. Thank you!

Pingback: A bit of Unity Serialization – Lunch Baller

Looking for part 2!

I will write it soon. Just moved to the US for a new job and I don’t have enough free time now.

Reblogged this on Dinesh Ram Kali..

Nice intro. For me, though, it’s missing the key part, showing the serialization of that class. serializer.serialize(file, MyBehavior) or whatever it should be in Unity. Looking forward to the next article.

Yeah, that is my plan for the next article, keep an eye or even better, subscribe 🙂